The Business Empire of Randomness: How Probability Questions Step Into the Commercial World

- Haruka Shuei

- Jul 14, 2021

- 7 min read

We’ve probably all been through this in secondary school: looking at a probability question like “when we row a dice, how likely will the outcome be 6?” for the first time and start to panic. These classical questions taught us the basic concept of probability, the measure of the likelihood of an event’s occurrence(Radke 2017). At that time, we were used to treating probability as pure mathematical questions apart from real life and struggled with permutation and combination problems at school. However, probability, or randomness, has long stepped into the commercial world and gradually become a strategy for businesses to attract consumers for higher revenue.

Probability-based business in real life: lottery vs mystery box

The lottery is probably one of the oldest and most well-known probability-based businesses. In the UK in 2019/2020, around 44% of 16+ citizens participate in a National Lottery Game at least once in the last 12 months ("Gambling and Lotteries - Taking Part Survey 2019/20"). The situation is similar in other developed countries, suggesting a high participation rate for national lotteries globally.

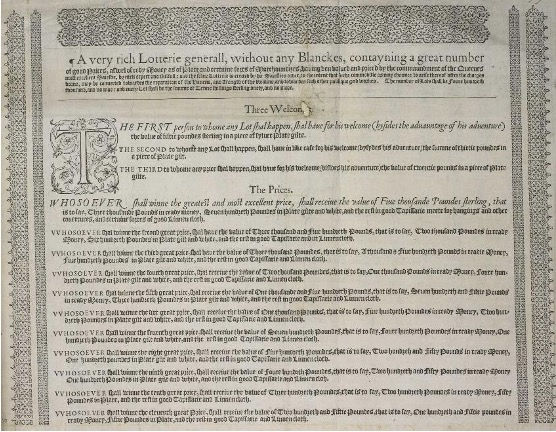

While personal gain seems to be the driving force on consumers’ side of the table, over on the suppliers’ side, the incentive is different. When the first national lottery developed in the UK in 1566, the initiative was to raise money for expansion on national export by funding constructions of the ships and ports. Around 400,000 lottery tickets were issued and each priced at 10 shillings, which would ideally generate ₤200,000 for the nation. The jackpot was ₤5,000, equivalent to ₤900,000 today, and paid in a mix of cash and expensive commodities such as linen cloth (The Health Lottery).

Although this first national lottery didn’t instantly collect the money needed as planned due to the difficulty of selling tickets around the country, this form of raising a great amount of money for the nation for good initiatives was passed on and can still be seen in national lotteries around the globe. In the US, for every single dollar spent on a lottery in New York, 34% of it goes to the public education system, 14% of it becomes income tax revenue for the state and the government, and only 31% of the jackpot goes to the winner as pure profit (CNBC 2019). With jackpots’ huge base number and continuing growth, up to billions of dollars, the portion used to support the public education system and the government is large.

Besides the lottery, other forms of probability-based businesses developed over time, only with similar settings of “jackpots” but leaving out the good initiatives. From the origin, mystery boxes, or loot boxes in the gaming community, are consumable virtual boxes that generate random skin and other items that gamers could use on their characters in the game (Shah 2021). For gamers, special and limited skins or weapons can be their “jackpots”.

While loot boxes are still popular among gamers, markets for physical mystery boxes start to grow. Loot Crate was one of the first companies to innovatively provide physical “loot boxes.” T-shirts, hats and other game-related contents are sold in the form of mystery boxes. This new form of mystery boxes that target a community of people sharing similar interests has expanded to almost every field imaginable. New “jackpots” are set based on the collective interests of the target community, including iPhone 12 Pro Max for electronic lovers and designer bags for the fashion community. Almost all communities are involved, of different age and gender.

From traditional lottery tickets to modern mystery boxes, the probability-based business has evolved and continues to thrive decades after decades, centuries after centuries. But why are people so obsessed with “probability questions” in real life? What are the secrets of adding randomness in businesses? Going back to the great example of lottery tickets, the idea and tricks become pretty clear.

How randomness makes money: the psychology of lottery

There are two major tricks. The first one starts with what participants care about when playing the lottery. In 2019, when a group of 123 UK youths aged 11-16 were asked why they bought National Lottery draw tickets, the popular answers were “It’s fun to play” that took 24% and “I have a chance to win a big prize” that took 15%. And this group of youth are also heavily affected by family members who play the lottery, with 24% of the answer being “my parents/ other family members play” (Gambling Comission 2019). This suggests youth playing the lottery is probably also a result of family influence.

If the sense of joy and the expectation is what the target groups need, then the companies try to increase the incentives and hold on to their consumers by increasing the size of the jackpots and decreasing the chance of winning. In 2002, Mega Millions, one of the largest multi-state lottery companies in the US, had jackpots as low as 12 million dollars and were handed out more often, leading to jackpot fatigues. In 2018, the minimum for a Mega Millions’s jackpot has gone up to 40 million and top prizes once grew to 1.54 billion dollars (CNBC 2019). Consequently, jackpots are handed out much less often. To many, especially low-income households, every lottery ticket can become a life-changing moment, so why not consume a chance of winning with just $2-3 a ticket?

The second trick takes advantage of the availability heuristic through designed marketing. Humans have the tendency, availability bias, to use the information they can recall quickly and easily to make future decisions (The Decision Lab 2020) and lottery companies make use of this fact to market their lotteries and attract consumers. They only market the stories of jackpot winners in the press to the target groups, highlighting the luxurious life the winners have after their wins. This leaves a strong impression to anyone interested in lottery tickets and especially those who have always dreamed of winning a jackpot. With this in mind, people are more likely to believe in their chance of winning while the chance of winning doesn’t change at all, leaving millions of “losers” behind the scene.

What can go wrong with randomness: ethics challenged by mystery boxes

Generally, mystery boxes are using the same tactics as the lottery, gradually adding more expensive prizes to the pool and emphasizing their values to specific consumers of interest. However, due to their very special nature and pure commercial purpose, the ethics of many mystery boxes become questionable.

Unlike normal goods and even lottery tickets from which consumers know what to expect after their consumption, mystery boxes are known for and named after the suspense created when opening a box with unknown items inside. Yet, this creative probability-based business also raises “creative” concerns: consumers may not like what they get from the mystery boxes, and some of the consumers may only pay for the suspense but not the item itself. This suggests besides its growth potentials, the mystery box market also has a high potential of generating waste. In China, Tmall, an online marketplace, reported in 2019 that over 200,000 Chinese consumers spend $3,100 on average on mystery boxes for collectable figurines (TONG 2021). Imagine how many packaging wastes have been created and, because of the non-refundable nature of the sense of mystery, how many of these figurines purchased have been discarded if not preferred by the collector. In the e-commerce world, the number can be huge and would continue to grow with the mystery box market.

Not only is the consumption pattern of mystery boxes questionable, the items included in mystery boxes are also challenging the ethics. Following the success of other industries in the mystery box market, more and more companies from other fields start to develop similar businesses. This soon results in a craze that is especially hot in China: everything can be put in mystery boxes. While consumers have a very wide range to choose from, mystery boxes become controversial. On the positive side, there’re plane ticket mystery boxes that cost 98RMB ($15.1) each with unknown date, unknown departure time and arrival time, and unknown destinations. This serves as a special promotion in the airline industry to generate higher revenue and recover from the trough of the pandemic. On the dark side, “pet mystery boxes” emerge and cause outrage. Delivering live animals by mail is illegal in China, but puppies and kittens are put into small crates and transferred by trucks. While having pets requires huge responsibility and takes time to let owners familiarize themselves with their pets, many of the pets are sent by mail by heartless sellers and die on their way to meet new owners.

Reflection on the economy of randomness

Have we gone too far for mystery boxes? Is the concept of the mystery box itself wrong? What should be the standards and regulations for mystery boxes and other probability-related business?

Clearly, mystery box has become a vigorous business and culture, unique in its nature and product. While companies can enjoy the commercial benefits from probability-related businesses and consumers can appreciate the sense of suspense and excitement in their consumer journeys, both sides should keep in mind that probability, as a commercial tool or a fun consumer experience, is an invisible layer of package in which the product is delivered. We should always bear in mind and be responsible for the true products, illusorily decorated and wrapped with probability, that we are (or might) be selling and buying.

Works Cited

"Availability Heuristic." The Decision Lab, 29 July 2020, thedecisionlab.com/biases/availability-heuristic/.

"Blind Boxes Unwrapped." TONG | Consultancy, Creative Agency & Social Commerce for China, 19 Jan. 2021, www.tongdigital.com/intelligence/blind-boxes-unwrapped.

CNBC. "How Mega Millions And Powerball Jackpots Grew So Large." YouTube, 1 June 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYxYSgg6JEI.

Dean, Jeremy. "Availability Heuristic: Why People Buy Lottery Tickets." PsyBlog, 12 June 2021, www.spring.org.uk/2021/06/availability-heuristic.php.

"Gambling and Lotteries - Taking Part Survey 2019/20." GOV.UK, 16 Sept. 2020, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/taking-part-201920-gambling-and-lotteries/gambling-and-lotteries-taking-part-survey-201920.

The Health Lottery. "Where Did the UK Lottery Start?" Online Lottery - Buy a Lottery Ticket for £1 - The Health Lottery - The Health Lottery, www.healthlottery.co.uk/blog/where-did-the-uk-lottery-start/.

Lehrer, Jonah. "The Psychology Of Lotteries." WIRED, 3 Feb. 2011, www.wired.com/2011/02/the-psychology-of-lotteries/. Accessed 17 June 2021.

Shah, Tobias. "The Evolution of Mystery Boxes." Hybe.com, 18 Feb. 2021, blog.hybe.com/the-evolution-of-mystery-boxes.

Westcott, Ben, et al. "Dead Puppies and Kittens in Crates Reveal the Dark Side of China's Mystery Box Craze." CNN, 20 May 2021, edition.cnn.com/2021/05/19/business/china-pet-mystery-box-intl-hnk-dst/index.html.

Gambling Commission. (2019). Young people and gambling survey 2019. A research study among 11-16 year olds in great britain.

Radke, Parag. "Basic Probability Theory and Statistics." Medium, 10 Oct. 2017, towardsdatascience.com/basic-probability-theory-and-statistics-3105ab637213.

.png)

Comments